(Photo: Sylvia Landeck)

Parish

Development and growth

The former parish of Zion and its church have always been closely linked to events in German history. An example of its historical relevance can be seen in the church’s efforts to relieve the social distress suffered by its parishioners. By way of contrast, the church’s culpability in its collaboration with the state during the Nazi period is also in evidence here, though it should be said that there was some courageous work done by individual Christians during that terrible time. The history of the Umwelt-Bibliothek (or “Environmental Library,” a dissident movement sponsored by the parish) illustrates some of the mechanisms by which the GDR’s totalitarian regime operated and illustrates how resistance to it emerged, at first failed and finally succeeded.

The Zionskirche now belongs to the Protestant parish of am Weinberg. The modern parish is currently growing through the recent influx of new young families: our Kindergarten has a long waiting list, while baptisms and weddings are a central part of the life of the community. Historically a notoriously poverty-stricken working class area, the neighbourhood has since become a popular residential zone. But the gentrification that the parish has experienced has also brought its own problems. The adjacent neighbourhood of Wedding, with its social difficulties and integration problems, can sometimes seem a world away. It is often said that the line that marks where the Berlin Wall one stood – only a few hundred metres from the Zionskirche – also marks out Germany’s most difficult to cross social boundary.

Critical (and self-critical) memory can often lead to the growth of a commitment to creating a socially well-balanced neighbourhood and to the fight against all forms of discrimination. And our community’s commitments also include our determination that the Zionskirche remains an open-door church in which visitors can experience faith at first hand and that it continue to provide a forum for political/social discussions and a space for art exhibitions.

2009 exhibition opening “20 Years Fall of the Berlin Wall” (Photo: Cordula Giese)

Architecture

The construction of the church

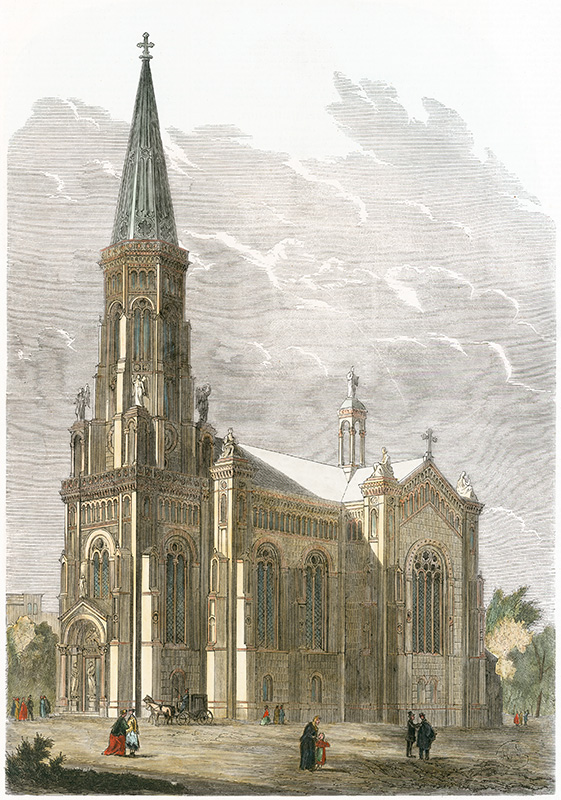

The church is located at the top of Berlin’s highest natural hill, on the site of a former vineyard – Mount Zion. The siting of the church on a five-cornered plaza at the intersection of three streets was so important to architect August Orth that he opted not to build the choir in its usual position towards the east. Then as now, the 67m steeple served as a landmark and vantage point over the city.

The building – Orth’s first church – is constructed in terracotta brick in the Berlin historicist style, decorated with richly ornamented facades. The large tracery windows are surmounted by a small neo-Romanesque gallery. The interior, which almost has the appearance of a traditional central-plan church, provides an unobstructed view of the altar and chancel. The gallery, with its large organ platform, runs all the way around the inside of the church.

The floor in the altar area is decorated in a rich carpet-like design. Due to its beauty and size, the Zionskirche was soon being referred to as “Cathedral of the North.” It was to become – just as its inaugurators expressed their aspirations for it during its consecration – a “place for contemplation, a feast for the eyes and heart.”

Zionskirche Berlin (Photos: Stefan Melchior, Kultur Büro Elisabeth)

Design drawing, 1865 (© Archive Zionskirche)

History

The beginnings of the Zionskirche

Once the process of industrialization had begun in Germany from 1830 onwards, Berlin was to evolve into a modern industrial centre within a few decades. The mechanical engineering sector in particular had an insatiable need for labour, attracting workers to settle in the Oranienburger and Rosenthaler Vorstadt in the northern suburbs of the city. Many of these new arrivals were cut off from their cultural and religious roots. In 1835, the King and the city administration commissioned renowned Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel to build the St. Elisabethkirche on Invalidenstraße.

The population continued to grow. In as little as 20 years, the number of parishioners was already so great in the parish of St. Elisabeth that it had to buy a hall on Schönhauser Allee, which it renamed the Zionskapelle (“Zion Chapel”), to provide church services. In 1864, “Zion” was bestowed the status of independent parish under the patronage of Wilhelm I. Just one year later, the parish already had 20,000 souls within its bounds. The parish described its situation thus: “The city’s largest contingent of proletariat and poverty can be found here.” The King was asked to “most graciously grant” a portion of the capital needed to construct a new church.

A portion of the building cost was approved and the church consistory initially commissioned building inspector Gustav Möller with planning the work, which it was to hand over to architect August Orth (1828–1901) in 1866. On 16th October 1866, the corner stone was laid on the site, which the widow of Christian Wilhelm Griebenow, the most important landowner in the area, had donated to the city as a gift. However, further funding was not forthcoming and construction soon petered out, eventually coming to a complete halt in 1868 once the exterior was complete. The parish annals list endless efforts to raise money from church and state authorities.

It was not until 1871, directly after victory in the Franco-Prussian War, that construction was re-commenced, using money from French reparation payments. The Zionskirche was consecrated in the presence of the German Emperor Wilhelm I and chancellor Otto von Bismarck on 2nd March 1873.

Zionskirche, around 1900 (© Archive Zionskirche)

Zion from 1873 to the foundation of the GDR

Pastor Julius Kraft, a man of strong personality, thereafter led and developed the parish for 37 years. To combat the social problems resulting from the difficult economic conditions of the time, the parish began to offer a variety of social services. It established a kindergarten in 1873 and provided pastoral support for Marthas Hof, an educational institution for girls founded in 1854. It also supported a variety of cultural and social associations. Its sphere of activities included running a Sunday school, a junior primary school and a soup kitchen.

A total of one thousand confirmations were recorded in 1888, a year in which there were 1500 children attending Sunday school. A total of four parishes had been established in the area by 1890. Three daughter churches had been built on Zion’s initiative by 1908 (the Friedenskirche, the Gethsemanekirche and the Segenskirche). Even with these changes, however, Zion was still serving as many as 40,000 parishioners. The hyperinflation of 1923 left much of the population in penury. In response, the parish facilitated a welfare organization, the Wohlfahrtsverband, to supply people with food from the sacristy of the Zionskirche.

The parish of Zion was severely affected by the Second World War. In November 1943, a fire bomb destroyed the church roof and caused extensive damage to the entire building. Makeshift repairs were made to the war-damaged building and, on 9th August 1953, the church was re-consecrated.

The anti-church propaganda of the GDR government increasingly hampered the work of the parish community and church life began to take place increasingly behind closed doors. Due to scarcities to which the East German economy was particularly prone, the structural damage to the Zionskirche continued to deteriorate.

Church interior, around 1930 (© Archive Zionskirche)

Umwelt-Bibliothek

A centre of the civil rights movement in the GDR

During the 1980s, the economic competition between Germany’s two systems was shifting ever more clearly against the GDR. The socialist planned economy conducted its manufacturing in obsolete factories, giving no thought to the environmental damage they were causing. This fact was becoming increasingly evident, though despite this discussion of the problem was frowned upon, particularly where it emanating from groups close to the church.

In 1986, the Umwelt-Bibliothek (or “Environmental Library”) first opened its doors in Zion’s rectory on 15/16 Griebenowstraße. After the Chernobyl disaster, a number young people got together to form a peace and environmental defence group in protest against nuclear energy. Pastor Hans Simon facilitated the intrepid work of these campaigners within the parish of Zion. Simon expressed his theological view as follows: “One can only speak about, think about, and believe in God responsibly, if one at the same time talks about man and his social, economic and political reality. … The church does not only exist for itself, but must impact on society with its work.”

The Umwelt-Bibliothek quickly developed into an important centre of opposition. Its members provided the impetus for networking processes among alternative political action groups in the GDR. They began publishing their Samizdat magazine, “Umweltblätter,” printing 150 copies per monthly issue. The magazine’s status as “internal church information” to some extent gave it legal cover. Discussion evenings, readings and exhibitions of the work of artists banned by the regime took place regularly in the Umwelt-Bibliothek’s gallery. The Library gave access to literature that the Socialist state withheld from its citizens. Its goal was to break the state’s monopoly on information relating to human rights, peace and the environment.

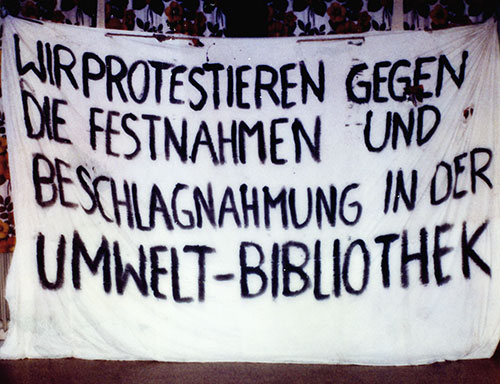

The constant monitoring and infiltration of the Stasi culminated in by a raid on 24th November 1987. Agents of the state security service forced their way into the rectory, searched the parish rooms and took seven people into custody. The raid precipitated a storm of protest, including solemn vigils, banners and intercessionary prayers, much of which activity was reported in the international media. The parish and the church authorities shielded the group and mediated for it. Public pressure quickly led to the release of the detainees. The action was to provide a signal to the civil rights movement throughout the GDR.

Banner of the Umwelt-Bibliothek

(© Archive Zionskirche)

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the parish of Zion

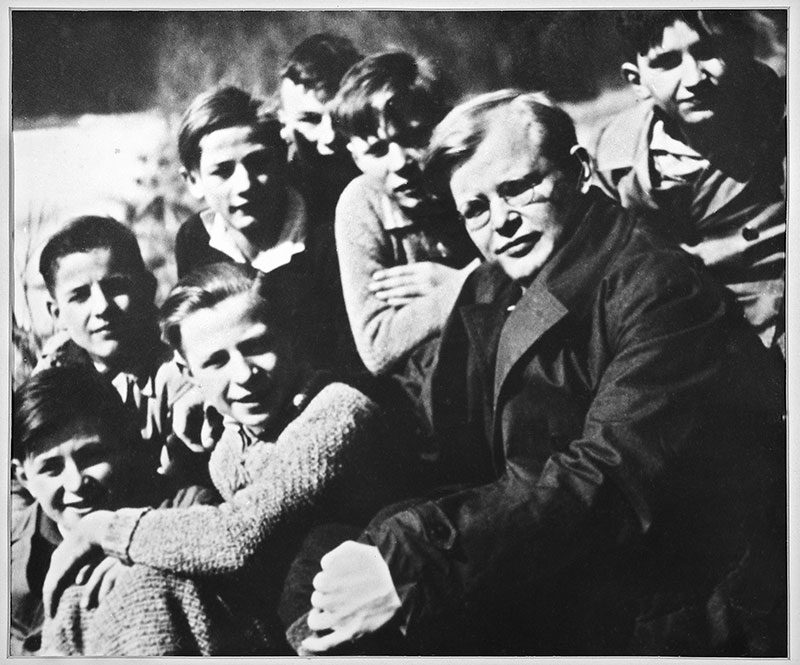

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a freshly ordained minister in November 1931 when first called to action by his Church. The parish of Zion was in urgent need of replacement staff. Bonhoeffer was asked to take over a class of confirmation candidates orphaned by the terminal illness of its previous teacher. In order to take better care of his charges, Bonhoeffer moved into a rented apartment at 61 Oderberger Straße. He wrote at the time, “… but what currently most occupies my mind is the confirmation lessons I am giving to 50 boys in the north of Berlin. This is about the wildest area in Berlin, suffering the city’s most difficult social and political conditions. At first, the boys behaved just appallingly – to the extent that I experienced real discipline problems for the first time. But one thing helped here too: that I simply recounted biblical material to the boys … Since I’ll be with the boys until their confirmation, I have to visit all 50 sets of parents and will be moving into the area for two months for this purpose. I am very much looking forward to this time. It is real work. The domestic conditions are mostly indescribable: poverty, disorder, and immorality.”

He was well aware of his church’s failures in facing up to the scandalous injustice of the social conditions of the time. The world depression and its accompanying unemployment were at their height. Against this background, he practiced the principle of “the Church for Others”: he was determined to be there for “his boys” at all times. He taught them chess and English. He bought material for their confirmation suits and cut it out himself, so that the kids could celebrate a dignified confirmation ceremony. After the ceremony, eight of the boys accompanied Bonhoeffer to his parents’ holiday home in the town of Friedrichsbrunn in the Harz mountains. It was the first holiday some of them had ever had in their lives.

Bonhoeffer was no longer working at Zionskirche when the Kirchenkampf (“Church Struggle”) broke out in 1933 over the state’s claim to control over the church. The dispute escalated within the church over its attitude towards the introduction of what were then known as the Aryan Paragraphs. Farsightedly – yet completely isolated in this stance – he wrote in April 1933 that “The church has an unconditional obligation toward the victims of any social stricture, even if they do not belong to the Christian community. … If the church allows the state to practice too much or too little law and order, it will find itself called not only to help the victims who have fallen under the wheel, but it will find that it has fallen into the spokes of the wheel itself.”

Bonhoeffer with confirmands

(© Archive Zionskirche)

I believe that God

can and wants to create

good out of everything,

even evil.

For that He needs people

who use everything

for the best.

can and wants to create

good out of everything,

even evil.

For that He needs people

who use everything

for the best.